Conspiracies and cover-ups are a dime a dozen in fictional films (thrillers, political dramas, you identify it). However when a documentary unravels a conspiracy, it could actually tackle the sort of hushed suspense these movies used to have and infrequently do anymore. (The heyday of conspiracy cinema, the ’70s period of “All of the President’s Males” and “Chinatown” and “The Dialog” and “The Parallax View,” was about 10,000 conspiracy films in the past.)

“The Stringer” is a documentary thriller a few lethal critical topic: the true authorship of the well-known Vietnam Conflict {photograph}, taken on June 8, 1972, within the city of Trảng Bàng, that confirmed the aftermath of a napalm assault — a 9-year-old woman named Phan Thį Kim Phúc working, bare, towards the digital camera, her arms outstretched like damaged wings, her mouth open in a scream of agony. She’d been burned throughout her physique (the shot exhibits 4 different youngsters, clothed and working together with her), and the {photograph}, from the second it went out into the world and was seen by billions, turned often called “Napalm Girl.” It is among the most iconic and devastating photographs of the horror of warfare ever seen.

“Naplam Woman” is acknowledged to be {a photograph} of immeasurable historic significance, one which had a profound affect on folks’s emotions concerning the Vietnam Conflict. (It’s generally stated that the picture helped finish the warfare; I’d say that’s one thing of an overstatement.) However who took the {photograph}? The morning after it was shot, when it was despatched out from the Saigon workplace of the Related Press, it was credited to Nick Út, a 21-year-old Vietnamese photographer who was the AP’s native employees photographer. Nearly in a single day, the {photograph} modified his life. From that second on, he turned celebrated for having taken one of the crucial iconic photographs of the twentieth century.

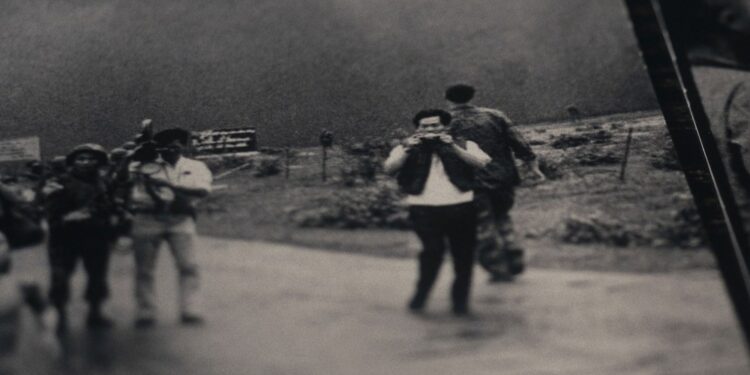

However “The Stringer,” directed by Bao Nguyen (“The Best Evening in Pop”) and government produced by Gary Knight, who spearheaded the two-year investigative journey the movie is about (Knight, tall and courtly and British, with a wedge of white hair, serves as its on-camera information and interviewer), claims that Nick Út was not the one who took the picture. Út was there that day, on that desolate strip of highway in Trảng Bàng, together with different movie cameramen and photographers. However the documentary asserts that the {photograph} was taken by Nguyen Thanh Nghe, a contract photographer who contributed photographs to the AP. He was there that day too.

The movie’s declare of what occurred is comparatively easy. It says that Horst Faas, the AP picture editor in Saigon, knew that Nghe had taken the picture, however after paying him the usual $20 for it Faas ordered the shot to be credited to Nick Út, as a result of he needed it to be an AP employees picture. In line with the movie, this form of factor occurred on a regular basis and was not thought of an enormous deal; it was half a system of “benign” exploitation. However with {a photograph} of this energy and magnitude, the re-crediting (if that’s what occurred) proved to be momentous.

It’s my job to say whether or not I feel a film is sweet or not, and let me say proper now that “The Stringer” is an excellent film: rapt, pressing, absorbing. However on this case it isn’t that easy. All the movie spins round a binary query: Did Nick Út take that picture? Or did Nguyen Thanh Nghe? And it’s unattainable to guage the movie in any significant manner with out judging its central thesis, which is basically a conspiracy concept: that credit score for the picture was stolen, and that this has all been coated up for 50 years. If that’s what occurred, it might be a scandal, a tragedy, perhaps a criminal offense.

Gary Knight, a photographer himself, leads the investigation, however the movie’s pivotal determine is Carl Robinson, who on the time was an AP picture editor. Robinson, now in his eighties, says that he was the one who swapped in a single photographer’s identify for one more after his boss, Horst Faas, ordered him to take action. And he claims that he sat on this secret, with a silent squirmy guilt, for 50 years.

Why didn’t he say something earlier than? It could have meant rocking the boat to the tenth energy; tossing a grenade into the center of a delicate cultural legacy; disrupting the lives of all those that had lied about it; and past that, he would have needed to go up in opposition to the AP, a information group that’s fiercely protecting of its personal legacy. The AP performed its personal six-month investigation into this case, which concerned interviewing seven witnesses, and the conclusion it got here to is that there was no conspiracy, no swapped picture credit score — that Nick Út was, actually, the photographer. The AP has has raised major objections to “The Stringer,” and Nick Út has threatened to take authorized motion in opposition to the filmmakers.

For some time, I watched “The Stringer” with my guard up, skeptical of its declare. Partly that’s as a result of the movie, fairly than taking the angle of “Oh, let’s examine this query,” operates proper out of the field from the point-of-view that the picture credit score was stolen. The movie gathers proof because it goes alongside, however it already appears to have made up its thoughts. And that put me on alert. On the similar time, I listened to Carl Robinson inform his story (about being ordered to falsify the picture credit score), and never solely does the story come off as convincing, however a query lingers in again of it: What would his motivation be to lie about this? The story he’s telling makes him look dangerous. Fox Butterworth, the fabled New York Occasions reporter (who thinks the movie’s thesis is unfaithful), has stated that he thinks Robinson is mendacity out of an animus towards his previous employer, the AP, which he parted methods with in 1978. However that looks like fairly a stretch. You fabricate this story now, 47 years later, all to take revenge on the group you labored for many years in the past?

Nick Út refused to be interviewed by the filmmakers (which could be an indication of one thing), and far of “The Stringer” is dedicated to their try and unearth the identification of the “different” photographer. Initially of the movie, they don’t know who he’s, or even when he’s lifeless or alive. “The Stringer” turns into a detective story. Carl Robinson’s spouse, who’s Vietnamese, claims that fifty years in the past it was an open secret amongst Vietnamese photographers that the picture credit score on “Naplam Woman” was stolen. And when Nguyen Thanh Nghe’s identify lastly bubbles to the floor, we begin to really feel a few of the catharsis triggered by a suspense drama. The filmmakers observe Nghe down in California, the place he has lived for many years, they usually fill in his biography. Lastly, Gary Knight sits down with him, and we hear his model of the occasions.

Nghe’s reminiscences provide no conclusive proof. But as viewers, we take him in — a person of mild pressure in his early 90s, with an air of radiant sincerity, his colleges very a lot intact, insisting with calm conviction that sure, he was the one who took the {photograph}, and sure, it was taken away from him. As soon as once more, we ask ourselves: If this isn’t the reality, then why would this previous man be mendacity? He evinces no want for controversy or glory. Why would his model of the occasions line up so precisely with Carl Robinson’s? There’s one element in Nghe’s story that’s haunting: He says that Horst Faas, on that fateful day, gave him a duplicate of the picture he’d taken, which Nghe then took dwelling, and his spouse was so upset by it that she destroyed it. In a while, it might need served because the proof of his authorship.

“The Stringer,” like every conspiracy thriller, makes us wish to consider. That’s a part of the character of a film like this one. But I’m an excessive amount of of a cynical skeptic to take that sort of dramatic impulse as something definitive. Watching a documentary like this one, what we wish, finally, isn’t emotion, and even an all-too-plausible argument. What we wish is proof. We wish it as residents watching a movie a few daunting photographic artifact. And in an odd manner we wish it as moviegoers, who’ve been conditioned by half a century of conspiracy cinema to anticipate a situation that culminates in a smoking gun.

Guess what? I’d say that “The Stringer” comes near having one. Midway by way of the film, we see all the important thing images that had been taken in these horrible minutes alongside the highway in Trảng Bàng, simply after the village space behind it had been bombed (mistakenly) by South Vietnamese Air Raiders. (That’s proper, the assault that “Napalm Woman” is a file of was a “pleasant hearth” incident, and U.S. forces weren’t concerned.) The 8 x 10 picture are assembled on a desk, and for second it’s possible you’ll suppose again to the sequence in Brian De Palma’s “Blow Out” the place the sound man performed by John Travolta assembles a bunch of nonetheless images right into a crude 20-second-long piece of shifting footage similar to the Zapruder movie. (Apropos of nothing, I’ve all the time discovered that scene to be the second I take a look at of “Blow Out” — a film I dislike intensely. As a result of how is it remotely believable {that a} mainstream journal, publishing stills from a Zapruder-type movie, would publish sufficient stills that you possibly can truly make a brief movie out of them?)

Because it seems, although, the photos-on-the-table sequence in “The Stringer” is merely the appetizer. The filmmakers hand all that materials over to a gaggle of forensic consultants in Paris, who do a meticulous computer-based evaluation, incorporating satellite tv for pc photographs, of which figures stood exactly the place and when throughout these essential couple of minutes in Trảng Bàng. On the movie’s climax, they current their evaluation, and it truly is like combing by way of the Zapruder movie, in search of that essential visible element that may all of the sudden convey the hidden actuality into focus.

We’re seeing photographs of what occurred — Kim Phúc working down that highway (which we additionally see in filmed shade footage). We’re seeing photographs of the photographers who had been there. And we’re seeing the images that they took. All of it has to trace in a spatial-temporal manner.

What the evaluation finally reveals is a determine, standing distant, in all probability 60 toes down the highway from Kim Phúc — in different phrases, too distant to have taken the “Napalm Woman” picture. The forensic group claims that that determine is Nick Út. Then we’re proven a number of photographs that that determine was within the precise place to have taken. And right here’s the kicker: These photographs had been AP photographs, credited to Nick Út. He took them. Which means that in terms of “Napalm Woman,” he couldn’t have been in the appropriate place on the proper time. “The Stringer” is a potent human story of daunting cultural resonance. However like all conspiracy situations, what it exerts is the cleaning fascination of actuality laid naked. It deserves to be seen — for the necessary truths which can be there in it, and for the sheer addictive pull of it.