BBC Korean in Hapcheon

BBC/Hyojung Kim

BBC/Hyojung KimAt 08:15 on August 6, 1945, as a nuclear bomb was falling like a stone by means of the skies over Hiroshima, Lee Jung-soon was on her approach to elementary college.

The now-88-year-old waves her palms as if attempting to push the reminiscence away.

“My father was about to go away for work, however he all of the sudden got here operating again and instructed us to evacuate instantly,” she recollects. “They are saying the streets had been full of the lifeless – however I used to be so shocked all I keep in mind is crying. I simply cried and cried.”

Victims’ our bodies “melted away so solely their eyes had been seen”, Ms Lee says, as a blast equal to fifteen,000 tons of TNT enveloped a metropolis of 420,000 folks. What remained within the aftermath had been corpses too mangled to be recognized.

“The atomic bomb… it is such a terrifying weapon.”

It has been 80 years since the US detonated ‘Little Boy’, humanity’s first-ever atomic bomb, over the centre of Hiroshima, immediately killing some 70,000 folks. Tens of 1000’s extra would die within the coming months from radiation illness, burns and dehydration.

The devastation wrought by the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki – which introduced a decisive finish to each World Conflict Two and Japanese imperial rule throughout massive swaths of Asia – has been well-documented over the previous eight a long time.

Much less well-known is the truth that about 20% of the speedy victims had been Koreans.

Korea had been a Japanese colony for 35 years when the bomb was dropped. An estimated 140,000 Koreans had been dwelling in Hiroshima on the time – many having moved there on account of pressured labour mobilisation, or to outlive below colonial exploitation.

Those that survived the atom bomb, together with their descendants, proceed to reside within the lengthy shadow of that day – wrestling with disfigurement, ache, and a decades-long combat for justice that is still unresolved.

Getty Photographs

Getty Photographs“No-one takes duty,” says Shim Jin-tae, an 83-year-old survivor. “Not the nation that dropped the bomb. Not the nation that failed to guard us. America by no means apologised. Japan pretends to not know. Korea isn’t any higher. They simply go the blame – and we’re left alone.”

Mr Shim now lives in Hapcheon, South Korea: a small county which, having turn out to be the house of dozens of survivors like he and Ms Lee, has been dubbed “Korea’s Hiroshima”.

For Ms Lee, the shock of that day has not light – it etched itself into her physique as sickness. She now lives with pores and skin most cancers, Parkinson’s illness, and angina, a situation stemming from poor blood move to the center, which generally manifests as chest ache.

However what weighs extra closely is that the ache did not cease along with her. Her son Ho-chang, who helps her, was recognized with kidney failure and is present process dialysis whereas awaiting a transplant.

“I consider it is on account of radiation publicity, however who can show it?” Ho-chang Lee says. “It is laborious to confirm scientifically – you’d want genetic testing, which is exhausting and costly.”

The Ministry of Well being and Welfare (MOHW) instructed the BBC that it had gathered genetic information between 2020 and 2024 and would proceed additional research till 2029. It will “contemplate increasing the definition of victims” to second- and- third-generation survivors solely “if the outcomes are statistically vital”, it stated.

The Korean toll

Of the 140,000 Koreans in Hiroshima on the time of the bombing, many had been from Hapcheon.

Surrounded by mountains with little farmland, it was a tough place to reside. Crops had been seized by the Japanese occupiers, droughts ravaged the land, and 1000’s of individuals left the agricultural nation for Japan in the course of the struggle. Some had been forcibly conscripted; others had been lured by the promise that “you might eat three meals a day and ship your youngsters to high school.”

However in Japan, Koreans had been second-class residents – usually given the toughest, dirtiest and most harmful jobs. Mr Shim says his father labored in a munitions manufacturing facility as a pressured labourer, whereas his mom hammered nails into wood ammunition crates.

Within the aftermath of the bomb, this distribution of labour translated into harmful and sometimes deadly work for Koreans in Hiroshima.

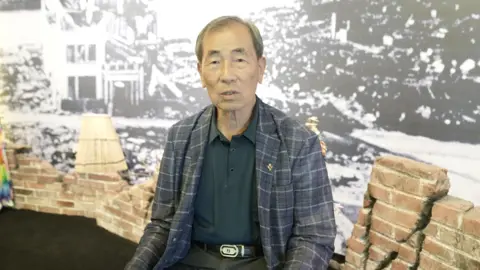

BBC/Hyojung Kim

BBC/Hyojung Kim“Korean employees needed to clear up the lifeless,” Mr Shim, who’s the director of the Hapcheon department of the Korean Atomic Bomb Victims Affiliation, tells BBC Korean. “At first they used stretchers, however there have been too many our bodies. Finally, they used dustpans to collect corpses and burned them in schoolyards.

“It was principally Koreans who did this. Many of the post-war clean-up and munitions work was performed by us.”

In keeping with a examine by the Gyeonggi Welfare Basis, some survivors had been pressured to clear rubble and recuperate our bodies. Whereas Japanese evacuees fled to kin, Koreans with out native ties remained within the metropolis, uncovered to the radioactive fallout – and with restricted entry to medical care.

A mix of those situations – poor therapy, hazardous work and structural discrimination – all contributed to a disproportionately excessive loss of life toll amongst Koreans.

In keeping with the Korean Atomic Bomb Victims Affiliation, the Korean fatality charge was 57.1%, in comparison with the general charge of about 33.7%.

About 70,000 Koreans had been uncovered to the bomb. By yr’s finish, some 40,000 had died.

Outcasts at dwelling

After the bombings, which led to Japan’s give up and Korea’s subsequent liberation, about 23,000 Korean survivors returned dwelling. However they weren’t welcomed. Branded as disfigured or cursed, they confronted prejudice even of their homeland.

“Hapcheon already had a leper colony,” Mr Shim explains. “And due to that picture, folks thought the bomb survivors had pores and skin ailments too.”

Such stigma made survivors keep silent about their plight, he provides, suggesting that “survival got here earlier than pleasure”.

Ms Lee says she noticed this “along with her personal eyes”.

“Individuals who had been badly burned or extraordinarily poor had been handled terribly,” she recollects. “In our village, some folks had their backs and faces so badly scarred that solely their eyes had been seen. They had been rejected from marriage and shunned.”

With stigma got here poverty, and hardship. Then got here sicknesses with no clear trigger: pores and skin ailments, coronary heart situations, kidney failure, most cancers. The signs had been in every single place – however no-one may clarify them.

Over time, the main target shifted to the second and third generations.

BBC/Hyojung Kim

BBC/Hyojung KimHan Jeong-sun, a second-generation survivor, suffers from avascular necrosis in her hips, and might’t stroll with out dragging herself. Her first son was born with cerebral palsy.

“My son has by no means walked a single step in his life,” she says. “And my in-laws handled me horribly. They stated, ‘You gave beginning to a crippled baby and also you’re crippled too—are you right here to spoil our household?’

“That point was absolute hell.”

For many years, not even the Korean authorities took lively curiosity in its personal victims, as a struggle with the North and financial struggles had been handled as larger priorities.

It wasn’t till 2019 – greater than 70 years after the bombing – that MOHW launched its first fact-finding report. That survey was principally based mostly on questionnaires.

In response to BBC inquiries, the ministry defined that previous to 2019, “There was no authorized foundation for funding or official investigations”.

However two separate research had discovered that second-generation victims had been extra weak to sickness. One, from 2005, confirmed that second-generation victims had been much more possible than the overall inhabitants to endure despair, coronary heart illness and anaemia, whereas one other from 2013 discovered their incapacity registration charge was practically double the nationwide common.

Towards this backdrop, Ms Han is incredulous that authorities maintain asking for proof to recognise her and her son as victims of Hiroshima.

“My sickness is the proof. My son’s incapacity is the proof. This ache passes down generations, and it is seen,” she says. “However they will not recognise it. So what are we purported to do – simply die with out ever being acknowledged?”

Peace with out apology

It was solely final month, on July 12, that Hiroshima officers visited Hapcheon for the primary time to put flowers at a memorial. Whereas former PM Yukio Hatoyama and different personal figures had come earlier than, this was the primary official go to by present Japanese officers.

“Now in 2025 Japan talks about peace. However peace with out apology is meaningless,” says Junko Ichiba, a long-time Japanese peace activist who has spent most of her life advocating for Korean Hiroshima victims.

She factors out, the visiting officers gave no point out or apology for a way Japan handled Korean folks earlier than and through World Conflict Two.

BBC/Hyojung Kim

BBC/Hyojung KimThough a number of former Japanese leaders have provided their apologies and regret, many South Koreans regard these sentiments as insincere or inadequate with out formal acknowledgement.

Ms Ichiba notes that Japanese textbooks nonetheless omit the historical past of Korea’s colonial previous – in addition to its atomic bomb victims – saying that “this invisibility solely deepens the injustice”.

This provides to what many view as a broader lack of accountability for Japan’s colonial legacy.

Heo Jeong-gu, director of the Crimson Cross’s assist division, stated, “These points… should be addressed whereas survivors are nonetheless alive. For the second and third generations, we should collect proof and testimonies earlier than it is too late.”

For survivors like Mr Shim it isn’t nearly being compensated – it is about being acknowledged.

“Reminiscence issues greater than compensation,” he says. “Our our bodies keep in mind what we went by means of… If we overlook, it’s going to occur once more. And sometime, there will be nobody left to inform the story.”