BBC Urdu

BBC/Farhat Javed

BBC/Farhat JavedSaira Baloch was 15 when she stepped right into a morgue for the primary time.

All she heard within the dimly-lit room have been sobs, whispered prayers and shuffling ft. The primary physique she noticed was a person who appeared to have been tortured.

His eyes have been lacking, his tooth had been pulled out and there have been burn marks on his chest.

“I could not have a look at the opposite our bodies. I walked out,” she recalled.

However she was relieved. It wasn’t her brother – a police officer who had been lacking for almost a yr since he was arrested in 2018 in a counter-terrorism operation in Balochistan, considered one of Pakistan’s most restive areas.

Contained in the morgue, others continued their determined search, scanning rows of unclaimed corpses. Saira would quickly undertake this grim routine, revisiting one morgue after one other. They have been all the identical: tube lights flickering, the air thick with the stench of decay and antiseptic.

On each go to, she hoped she wouldn’t discover what she was on the lookout for – seven years on, she nonetheless hasn’t.

BBC/Nayyar Abbas

BBC/Nayyar AbbasActivists say 1000’s of ethnic Baloch individuals have been disappeared by Pakistan’s safety forces within the final 20 years – allegedly detained with out due authorized course of, or kidnapped, tortured and killed in operations in opposition to a decades-old separatist insurgency.

The Pakistan authorities denies the allegations, insisting that most of the lacking have joined separatist teams or fled the nation.

Some return after years, traumatised and damaged – however many by no means come again. Others are present in unmarked graves which have appeared throughout Balochistan, their our bodies so disfigured they can’t be recognized.

After which there are the ladies throughout generations whose lives are being outlined by ready.

Younger and outdated, they participate in protests, their faces lined with grief, holding up fading pictures of males now not of their lives. When the BBC met them at their properties, they provided us black tea – Sulemani chai – in chipped cups as they spoke in voices worn down by sorrow.

A lot of them insist their fathers, brothers and sons are harmless and have been focused for talking out in opposition to state insurance policies or have been taken as a type of collective punishment.

BBC/Farhat Javed

BBC/Farhat JavedSaira is considered one of them.

She says she began going to protests after asking the police and pleading with politicians yielded no solutions about her brother’s whereabouts.

Muhammad Asif Baloch was arrested in August 2018 together with 10 others in Nushki, a metropolis alongside the border with Afghanistan. His household discovered after they noticed him on TV the following day, trying scared and baggy.

Authorities mentioned the lads have been “terrorists fleeing to Afghanistan”. Muhammad’s household mentioned he was having a picnic with buddies.

Saira says Muhammad was her “greatest buddy”, humorous and all the time cheerful – “My mom worries that she’s forgetting his smile.”

The day he went lacking, Saira had aced a college examination and was excited to inform her brother, her “greatest supporter”. Muhammad had inspired her to attend universty in Quetta, the provincial capital.

“I did not know again then that the primary time I would go to Quetta, it will be for a protest demanding his launch,” Saira says.

Three of the lads who have been detained alongside together with her brother have been launched in 2021, however they haven’t spoken about what occurred.

Muhammad by no means got here house.

Lonely highway into barren lands

The journey into Balochistan, in Pakistan’s south-west, appears like you might be moving into one other world.

It’s huge – overlaying about 44% of the nation, the most important of Pakistan’s provinces – and the land is wealthy with fuel, coal, copper and gold. It stretches alongside the Arabian Sea, throughout the water from locations like Dubai, which has risen from the sands into glittering, monied skyscrapers.

However Balochistan stays caught in time. Entry to many elements is restricted for safety causes and overseas journalists are sometimes denied entry.

It is also troublesome to journey round. The roads are lengthy and lonely, chopping via barren hills and desert. Because the infrastructure thins out the additional you journey, roads are changed by filth tracks created by the few autos that go.

Electrical energy is sporadic, water even scarcer. Colleges and hospitals are dismal.

Within the markets, males sit exterior mud retailers ready for patrons who not often come. Boys, who elsewhere in Pakistan might dream of a profession, solely speak of escape: fleeing to Karachi, to the Gulf, to anyplace that gives a manner out of this sluggish suffocation.

BBC/Nayyar Abbas

BBC/Nayyar Abbas Getty Pictures

Getty PicturesBalochistan turned part of Pakistan in 1948, within the upheaval that adopted the partition of British India – and regardless of opposition from some influential tribal leaders, who sought an unbiased state.

Among the resistance turned militant and, over time, it has been stoked by accusations that Pakistan has exploited the resource-rich area with out investing in its improvement.

Militant teams just like the Balochistan Liberation Military (BLA), designated a terrorist group by Pakistan and different nations, have intensified their assaults: bombings, assassinations and ambushes in opposition to safety forces have turn out to be extra frequent.

Earlier this month, the BLA hijacked a train in Bolan Pass, seizing hundreds of passengers. They demanded the discharge of lacking individuals in Balochistan in return for releasing hostages.

The siege lasted over 30 hours. In response to authorities, 33 BLA militants, 21 civilian hostages and 4 navy personnel have been killed. However conflicting figures recommend many passengers stay unaccounted for.

The disappearances within the province are broadly believed to be a part of Islamabad’s technique to crush the insurgency – but in addition to suppress dissent, weaken nationalist sentiment and assist for an unbiased Balochistan.

Lots of the lacking are suspected members or sympathisers of Baloch nationalist teams that demand extra autonomy or independence. However a big quantity are extraordinary individuals with no recognized political affiliations.

BBC/Farhat Javed

BBC/Farhat JavedBalochistan’s Chief Minister Sarfaraz Bugti informed the BBC that enforced disappearances are a difficulty however dismissed the concept they have been occurring on a big scale as “systematic propaganda”.

“Each baby in Balochistan has been made to listen to ‘lacking individuals, lacking individuals’. However who will decide who disappeared whom?

“Self-disappearances exist too. How can I show if somebody was taken by intelligence companies, police, FC, or anybody else or me otherwise you?”

Pakistan’s navy spokesperson Lieutenant Basic Ahmed Sharif just lately mentioned in a press convention that the “state is fixing the problem of lacking individuals in a scientific method”.

He repeated the official statistic typically shared by the federal government – of the greater than 2,900 instances of enforced disappearances reported from Balochistan since 2011, 80% had been resolved.

Activists put the determine larger – at round 7,000 – however there isn’t any single dependable supply of information and no option to confirm both aspect’s claims.

‘Silence will not be an possibility’

Ladies like Jannat Bibi refuse to just accept the official quantity.

She continues to seek for her son, Nazar Muhammad, who she claims was taken in 2012 whereas consuming breakfast at a resort.

“I went in all places on the lookout for him. I even went to Islamabad,” she says. “All I acquired have been beatings and rejection.”

The 70-year-old lives in a small mud home on the outskirts of Quetta, not removed from a symbolic graveyard devoted to the lacking.

Jannat, who runs a tiny store promoting biscuits and milk cartons, typically cannot afford the bus fare to attend protests demanding details about the lacking. However she borrows what she will so she will maintain going.

“Silence will not be an possibility,” she says.

BBC/Nayyar Abbas

BBC/Nayyar AbbasMost of those males – together with these whose households we spoke to – disappeared after 2006.

That was the yr a key Baloch chief, Nawab Akbar Bugti, was killed in a navy operation, resulting in an increase in anti-state protests and armed rebel actions.

The federal government cracked down in response – enforced disappearances elevated, as did the variety of our bodies discovered on the streets.

In 2014, mass graves of lacking individuals have been found in Tootak – a small city close to town of Khuzdar, the place Saira lives, 275km (170 miles) south of Quetta.

The our bodies have been disfigured past identification. The pictures from Tootak shook the nation – however the horror was no stranger to individuals in Balochistan.

Mahrang Baloch’s father, a well-known nationalist chief who fought for Baloch rights, had disappeared in early 2009. Abdul Gaffar Langove had labored for the Pakistani authorities however left the job to advocate for what he believed could be a safer Balochistan.

Three years later Mahrang acquired a telephone name that his physique had been present in Lasbela district within the south of the province.

“When my father’s physique arrived, he was carrying the identical garments, now torn. He had been badly tortured,” she says. For 5 years, she had nightmares about his last days. She visited his grave “to persuade myself that he was now not alive and that he was not being tortured”.

She hugged his grave “hoping to really feel him, but it surely did not occur”.

When he was arrested, Mahrang used to write down him letters – “numerous letters and I might draw greeting playing cards and ship them to him on Eid”. However he returned the playing cards, saying his jail cell was no place for such “stunning” playing cards. He wished her to maintain them at house.

“I nonetheless miss his hugs,” she says.

BBC/Nayyar Abbas

BBC/Nayyar AbbasAfter her father’s dying, Mahrang says, her household’s world “collapsed”.

After which in 2017, her brother was picked up by safety forces, in line with the household, and detained for almost three months.

“It was terrifying. I made my mom consider that what occurred to my father would not occur to my brother. But it surely did,” Mahrang says. “I used to be afraid of my telephone, as a result of it is perhaps information of my brother’s physique being discovered someplace.”

She says her mom and she or he discovered energy in one another: “Our tiny home was our most secure place, the place we might typically sit and cry for hours. However exterior, we have been two robust ladies who could not be crushed.”

It was then that Mahrang determined to battle in opposition to enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings. In the present day, the 32-year-old leads the protest motion regardless of dying threats, authorized instances and journey bans.

“We wish the appropriate to stay on our personal land with out persecution. We wish our sources, our rights. We wish this rule of concern and violence to finish.”

BBC/Farhat Javed

BBC/Farhat JavedMahrang warns that enforced disappearances gasoline extra resistance, slightly than silence it.

“They suppose dumping our bodies will finish this. However how can anybody overlook shedding their beloved one this fashion? No human can endure this.”

She calls for institutional reforms, guaranteeing that no mom has to ship her baby away in concern. “We do not need our youngsters rising up in protest camps. Is that an excessive amount of to ask?”

Mahrang was arrested on Saturday morning, a number of weeks after her interview with the BBC.

She was main a protest in Quetta after 13 unclaimed our bodies – feared to be lacking individuals – have been buried within the metropolis. Authorities claimed they have been militants killed after the Bolan Cross practice hijacking, although this might not be independently verified.

Earlier Mahrang had mentioned: “I could possibly be arrested anytime. However I do not concern it. That is nothing new for us.”

And at the same time as she fights for the long run she desires, a brand new technology is already on the streets.

Masooma, 10, clutches her faculty bag tightly as she weaves via the group of protesters, her eyes scanning each face, trying to find one that appears like her father’s.

“As soon as, I noticed a person and thought he was my father. I ran to him after which realised he was another person,” she says.

“Everybody’s father comes house after work. I’ve by no means discovered mine.”

Masooma was simply three months outdated when safety forces allegedly took her father away throughout a late-night raid in Quetta.

Her mom was informed he would return in a number of hours. He by no means did.

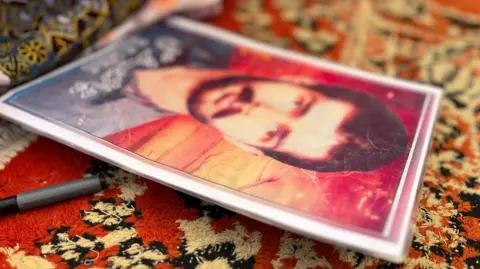

BBC/Farhat Javed

BBC/Farhat Javed BBC/Farhat Javed

BBC/Farhat JavedIn the present day, Masooma spends extra time at protests than within the classroom. Her father’s {photograph} is all the time together with her, tucked safely in her faculty bag.

Earlier than each lesson begins, she takes it out and appears at it.

“I all the time surprise if my father will come house immediately.”

She stands exterior the protest camp, chanting slogans with the others, her small body misplaced within the crowd of grieving households.

Because the protest involves an finish she sits cross-legged on a skinny mat in a quiet nook. The noise of slogans and site visitors fades as she pulls out her folded letters – letters she has written however may by no means ship.

Her fingers tremble as she smooths out the creases, and in a fumbling, unsure voice, she begins to learn them.

“Pricey Baba Jan, when will you come again? Each time I eat or drink water, I miss you. Baba, the place are you? I miss you a lot. I’m alone. With out you, I can’t sleep. I simply need to meet you and see your face.”